Kampala

Kampala | |

|---|---|

From left to right: Kampala skyline, Bahá'í House of Worship on Kikaaya Hill, Uganda National Mosque, Makerere University main building, skyscraper in central business district, and view over Lake Victoria | |

| Coordinates: 00°18′49″N 32°34′52″E / 0.31361°N 32.58111°ECoordinates: 00°18′49″N 32°34′52″E / 0.31361°N 32.58111°E | |

| Country | Uganda |

| District | Kampala |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Erias Lukwago |

| • Executive director | Jennifer Musisi[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 189 km2 (73 sq mi) |

| • Land | 176 km2 (68 sq mi) |

| • Water | 13 km2 (5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,190 m (3,900 ft) |

| Population (2014 Census) | |

| • Total | 1,507,080 |

| • Density | 7,928/km2 (20,530/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Kampalan, Kampalese |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Website | www.kcca.go.ug |

Kampala is the capital and largest city of Uganda. The city is divided into five boroughs that oversee local planning: Kampala Central Division, Kawempe Division, Makindye Division, Nakawa Division, and Rubaga Division. Surrounding Kampala is the rapidly growing Wakiso District, whose population more than doubled between 2002 and 2014 and now stands at over 2 million.[2]

Kampala was named the 13th fastest growing city on the planet, with an annual population growth rate of 4.03 percent,[3] by City Mayors. Kampala has been ranked the best city to live in East Africa[4] ahead of Nairobi and Kigali by Mercer, a global development consulting agency based in New York City.

Contents

Etymology[edit]

Before the arrival of the British colonists, the Kabaka of Buganda had chosen the zone that would become Kampala as a hunting reserve. The area, composed of rolling hills with grassy wetlands in the valleys, was home to several species of antelope, particularly impala. When the British arrived, they called it "Hills of the Impala". The language of the Baganda, Luganda, adopted many English words because of their interactions with the British. The Baganda translated "Hill of the Impala" as Akasozi ke'Empala – "Kasozi" meaning "hill", "ke" meaning "of", and "empala" the plural of "impala". In Luganda, the words "ka'mpala" mean "that is of the impala", in reference to a hill, and the single word "Kampala" was adopted as the name for the city that grew out of the Kabaka's hills.[5]

History[edit]

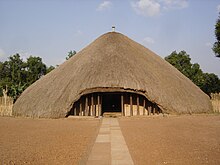

The city grew as the capital of the Buganda kingdom, from which several buildings survive, including the Kasubi Tombs (built in 1881), the Lubiri Palace, the Buganda Parliament and the Buganda Court of Justice. In 1890, British colonial administrator Frederick Lugard constructed a forum along Mengo Hill within the city, which allowed for the British to occupy much of the territory controlled by the Baganda, including Kampala.[6] In 1894, the British government officially established a protectorate within this territory, and in 1896, the protectorate expanded to cover the Ankole, Toro Kingdom, and Bunyoro kingdoms as well.[7] In 1905, the British government formally declared the entire territory to be a British colony.[8] From that time until the independence of the country in 1962, the capital was relocated to Entebbe, although the city continued to be the primary economic and manufacturing location for Uganda.[9] In 1922, the Makerere Technical Institute, now known as Makerere University, started as the first collegiate institution both within Kampala, and within the British colonies on the east coast of Africa.[9] Following the 1962 independence, Milton Obote became president of Uganda, and held the position until 1971, when former sergeant Idi Amin deposed his government in a military coup.[8] Idi Amin proceeded to expel all Asian residents living within Kampala, and attacked the Jewish population living within the city.[8] In 1978, he invaded the neighboring country of Tanzania, and in turn, the government there started the Uganda–Tanzania War, which created severe damage to the buildings of Kampala.[10] The city has since then been rebuilt with new construction of hotels, banks, shopping malls, educational institutions, and hospitals and the improvement of war torn buildings and infrastructure. Traditionally, Kampala was a city of seven hills, but over time it has come to have a lot more.[11]

Geography[edit]

Climate[edit]

Kampala has a tropical rainforest climate (Af) under the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system.[12]

A facet of Kampala's weather is that it features two annual wetter seasons. While the city does not have a true dry season month, it experiences heavier precipitation from August to December and from February to June. However, it's between February and June that Kampala sees substantially heavier rainfall per month, with April typically seeing the heaviest amount of precipitation at an average of around 169 millimetres (6.7 in) of rain. Kampala has been frequently mentioned as a lightning-strike capital of the world.

| Climate data for Kampala | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33 (91) |

36 (97) |

33 (91) |

33 (91) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

36 (97) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.6 (83.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

14 (57) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

14 (57) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 68.4 (2.69) |

63.0 (2.48) |

131.5 (5.18) |

169.3 (6.67) |

117.5 (4.63) |

69.2 (2.72) |

63.1 (2.48) |

95.7 (3.77) |

108.4 (4.27) |

138.0 (5.43) |

148.7 (5.85) |

91.5 (3.60) |

1,264.3 (49.77) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.8 | 5.1 | 9.5 | 12.2 | 10.9 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.4 | 93.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 68.5 | 73 | 78.5 | 80.5 | 78.5 | 77.5 | 77.5 | 75.5 | 73.5 | 73 | 71.5 | 74.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155 | 170 | 155 | 120 | 124 | 180 | 186 | 155 | 150 | 155 | 150 | 124 | 1,824 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization,[13] Climate-Data.org for mean temperatures[12] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: BBC Weather[14] | |||||||||||||

Sites of interest[edit]

The main campus of Makerere University is in the Makerere Hill area of the city.

Kampala also hosts the headquarters of the East African Development Bank on Nakasero Hill and the Uganda Local Governments Association on Entebbe Road.

Kampala was originally built on seven hills, but as its size has increased, it has expanded to more hills than seven. The original seven hills are:

- The first hill in historical importance is Kasubi Hill.

- The second is Mengo Hill.

- The third is Kibuli Hill, which is home to the Kibuli Mosque.

- The fourth is Namirembe Hill, home to the Namirembe Anglican Cathedral.

- The fifth is Lubaga Hill, the site of the Rubaga Catholic Cathedral.

- The sixth is Nsambya Hill.

- The seventh is Mbuya Hill.

- The eighth is Mutungo Hill.

- The ninth is Kampala Hill (Old Kampala). A mosque was built with monetary assistance from Libya on the hill in 2003, with a seating capacity of 15,000 people. The completed mosque was opened officially in June 2007.[15]

The city spread to Nakasero Hill, where there are international hotels, including the Kampala Speke Hotel, the Grand Imperial Hotel, the Kampala Intercontinental Hotel, the Imperial Royale Hotel, the Kampala Serena Hotel, the Kampala Sheraton Hotel, and The Pearl of Africa Hotel Kampala.[16]

There are also Tank Hill and Mulago Hill. The city is expanding rapidly to include Makindye Hill and Konge Hill.

Other features of the city include the Uganda Museum, the Ugandan National Theatre, Nakasero Market, and St. Balikuddembe Market (formerly Owino Market). Kampala is also known for its nightlife,[17] which includes several casinos, notably Casino Simba in the Garden City shopping centre, Kampala Casino, and Mayfair Casino. Port Bell on the shores of Lake Victoria is 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away.

Kampala hosts a Bahá'í House of Worship known as the Mother Temple of Africa and is situated on Kikaya Hill on the outskirts of the city. The temple was inaugurated in January 1961.[18]

The Ahmadiyya Central Mosque in Kampala is the central mosque of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which has six minarets and can hold up to 9,000 worshippers.[19]

While more than 30 percent of Kampala's inhabitants practice urban agriculture, the city of Kampala donated 32 acres (13 ha) to promote urban agriculture in the northeastern parish of Kyanja, in Nakawa Division.[20]

Demographics[edit]

The population of Kampala grew from 1,189,142 in 2002 to 1,507,080 in 2014.[21]

Kampala has a diverse ethnic population. The city's ethnic makeup has been defined by political and economic factors. A large number of western Ugandans, particularly the Banyankole, moved to the capital in the new government of Yoweri Museveni.[22]

Inter-tribal marriage in Uganda is still uncommon outside large urban centers. Although many Kampala residents have been born and brought up in the city, they still define themselves by their tribal roots and speak their ancestral languages. This is more evident in the suburbs, where tribal languages are spoken widely alongside English, Luganda, and Swahili (more recently introduced). In addition to the Baganda and Banyankole, other large ethnic groups include the Basoga, Bafumbira, Batoro, Bakiga, Alur, Bagisu (better known as Bamasaba), Banyoro, Iteso, Langi, and Acholi.[23]

Culture[edit]

Cultural institutions[edit]

Ndere Cultural Centre[edit]

A prominent cultural centre in the Kampala area of Kisasi that aims to promote Ugandan and African cultural expressions through music, dance and drama. The name Ndere is derived from the noun 'endere', which means flute. As an instrument found in all cultures, it is chosen as a peaceful symbol of the universality of cultural expressions.The Ndere centre is famous for its Ndere troupe, a music and dance troupe that perform several nights every week at the centre showcasing music and dance from all over Uganda as well as Rwanda and Burundi.[24]

People[edit]

Notable people[edit]

- Nancy Kacungira, presenter and reporter at the BBC World News, winner of the first ever BBC Komla Dumor Award.

- Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, Ugandan politician, businessman, entrepreneur, philanthropist and musician

- Micheal Azira, Ugandan footballer who plays for the Colorado Rapids in Major League Soccer.

- Allen Kagina, Executive Director, Uganda National Roads Authority, UNRA

- Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, British journalist and author

- Cornelius Edwards, former boxer

- Richard Gibson, British actor

- Mandy Juruni, basketball coach

- Aamito Lagum, fashion model, winner of the first season of Africa's Next Top Model

- John Mugabi, world champion boxer[25]

- Muteesa I, the 30th Kabaka of Buganda

- Muwenda Mutebi II of Buganda, the 36th Kabaka of Buganda

- Rajat Neogy, Ugandan-Indian journalist, writer, poet and founder and editor of Transition Magazine

- Shimit Amin Uganda-born Indian filmmaker

- Sudhir Ruparelia Ugandan entrepreneur and builder, Founder Chairman of Ruparelia Group

- Paulo Muwanga, former president and prime minister

- Denis Onyango, footballer

- Samuel Sejjaaka, professor

- Wasswa Serwanga, American football player

- Marcel Theroux, British novelist

- Erias Lukwago, Ugandan lawyer and politician

- Phiona Mutesi, chess prodigy and subject of the 2012 book and 2016 Disney film "Queen of Katwe"

- Martin Ssempa, pastor-doctor and head of a large congregation

- Pione Sisto, footballer, Ugandan born Danish footballer, currently playing for Spanish Club Celta Vigo

- John Sentamu, Archbishop of York

Honorary citizens[edit]

People awarded the honorary citizenship of Kampala are:

| Date | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2017 | Aga Khan IV (1936–Present) | British Humanitarian and Imam of Nizari-Ismaili Shia Islam.[26][27] |

Sports[edit]

Kampala is home to the City Oilers, one of East Africa's top basketball club teams. It is the only East African team that competes in the FIBA Africa Clubs Champions Cup. The Oilers play their home games in the MTN Arena, which is based in Kampala's Lugogo Area.[28]

Economy and infrastructure[edit]

Efforts are underway to relocate heavy industry to the Kampala Business and Industrial Park, located in Namanve, Mukono District, approximately 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) east of the city's central business district,[29] thereby cutting down on city traffic congestion. Some of the businesses that maintain their headquarters in the city center include all of the 25 commercial banks licensed in Uganda; the New Vision Group, the leading news media conglomerate and majority owned by the government; and the Daily Monitor publication, a member of the Kenya-based Nation Media Group. Air Uganda maintained its headquarters in an office complex on Kololo Hill in Kampala.[30] Crown Beverages Limited, the sole Pepsi-Cola franchise bottler in the country, is situated in Nakawa, a division of Kampala, about 5 kilometres (3 mi), east of the city centre.[31]

The informal sector is a large contributor to Kampala's GDP. Citizens who work in the formal sector also participate in informal activities to earn more income for their families. A public servant in Kampala, for example, may engage in aviculture in addition to working in the formal sector. Other informal fields include owning taxis and urban agriculture. The use of Kampala's wetlands for urban farming has increased over the past few decades. It connects the informal rural settlements with the more industrialized parts of the city. The produce grown in the wetlands is sold in markets in the urban areas.[32]

In December 2015, Google launched its first wi-fi network in Kampala.[33]

Transport[edit]

Kampala is served by Entebbe International Airport, which is the largest airport in Uganda.

Boda-bodas (local motorbike transport) are a popular mode of transport that gives access to many areas within and outside the city. Standard fees for these range from USh:1,000 to 2,000 or more. Boda-bodas are useful for passing through rush-hour traffic, although many are poorly maintained and dangerous.[34]

In early 2007, it was announced that Kampala would remove commuter taxis from its streets and replace them with a comprehensive city bus service. (In Kampala, the term "taxi" refers to a 15-seater minibus used as public transport.) The bus service was expected to cover the greater Kampala metropolitan area including Mukono, Mpigi, Bombo, Entebbe, Wakiso and Gayaza. As of December 2011[update] the service had not yet started.[35] Having successfully completed the Northern Bypass, the government, in collaboration with its stakeholders, now plans to introduce the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system in Kampala by 2014. On 12 March 2012, Pioneer Easy Bus Company, a private transport company, started public bus service in Kampala with an estimated 100 buses each with a 60-passenger capacity (30 seated and 30 standing), acquired from China. Another 422 buses were expected in the country in 2012 to complement the current fleet. The buses operate 24 hours daily. The company has a concession to provide public transport in the city for the next five years.[36][37] The buses were impounded for back taxes in December 2013. The company expected to resume operation in February 2015.[38]

In 2014, Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni and a China transportation company signed a Memorandum of Understanding, that they would at some point begin embarking on building a light rail system in Kampala, similar to the one recently completed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

On 11 April 2011, the pressure group Activists for Change (A4C) held its first Walk to Work protest near Kampala, in response to a comment by President Museveni on the increased cost of fuel, which had risen by 50 percent between January and April 2011. He said: "What I call on the public to do is to use fuel sparingly. Don't drive to bars."[39][40] The protest, which called on workers to walk to work to highlight the increased cost of transport in Uganda,[39] was disrupted by police, who fired tear gas and arrested three-time presidential candidate Kizza Besigye and Democratic Party leader Norbert Mao.[41] In the course of the protest, Besigye was shot in the right arm by a rubber bullet. The government blamed the violence on protesters.[40]

In 2016, the Rift Valley Railways Consortium (RVR) and Kampala Capital City Authority established passenger rail service between Namanve and Kampala and between Kampala and Kyengera. Those services were temporarily discontinued after RVR lost its concession in Uganda in October 2017.[42] However, when Uganda Railways Corporation took over the operations of the metre gauge railway system in Uganda in 2018, the service was restored in February that year.[43] A new Kampala to Port Bell route is being planned, to be added in the 2018/2019 financial year.[42]

gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Vision, Reporter (19 April 2011). "Kampala Executive Director Takes Office". New Vision. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Uganda: Administrative Division". Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "City Mayors: World's fastest growing urban areas (1)". www.citymayors.com.

- ^ "Kampala ranked best city in East Africa".

- ^ "Kampala: Origin of The Name". Myetymology.com. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Kampala, Uganda (1890- ) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "HISTORY OF UGANDA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c (http://www.hydrant.co.uk), Site designed and built by Hydrant. "Uganda : History | The Commonwealth". thecommonwealth.org. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Kampala, Uganda (1890- ) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "HISTORY OF UGANDA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "History of the City of Kampala". Ugandatravelguide.com. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Climate: Kampala – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Kampala". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Average Conditions Kampala, Uganda". BBC Weather. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Madinah Tebajjukira, and Charles Ariko (9 June 2007). "Libyans Open Old Kampala Mosque". New Vision. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Musoke, Ronald (6 February 2017). "Uganda: Aya Hotel - Rezidor Hotel Chain Replaces Hilton". The Independent (Uganda) via AllAfrica.com. Kampala. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Azzarito, Amy. "Where to Party in Kampala, the City That (Really) Never Sleeps".

- ^ "Fifty years on, Uganda's Baha'i temple stands as a symbol of unity and progress – Bahá'í World News Service (BWNS)". 18 January 2011.

- ^ Ahmadiyya Muslim Mosques Around the World, pg. 112

- ^ Wolfe, J. M., & McCans, S. (2009). DESIGNING FOR URBAN AGRICULTURE IN AN AFRICAN CITY: KAMPALA, UGANDA. Open House International, 34

- ^ UBOS. "National Population and Housing Census 2014 Main Report" (PDF). Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Jones, Ben (2 April 2009). "Museveni's Rule Has Divided Uganda". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Ethnic Groups of Uganda". Cia.gov. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Ndere centre, where African culture is very alive". www.newvision.co.ug. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ BRC (3 February 2016). "John Mugabi: Biography". Boxrec.com (BRC). Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ https://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1455722/kcca-award-aga-khan-honorary-citizenship

- ^ https://allafrica.com/stories/201706160199.html

- ^ Juruni eyes 2013 Basketball crown, NewVision.co.ug, 17 May 2013. Accessed 16 May 2017.

- ^ GFC (3 February 2016). "Distance between Kampala Road, Kampala, Central Region, Uganda and Namanve Industrial Park, Mukono, Central Region, Uganda". Globefeed.com (GFC). Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Vision Reporter (23 February 2009). "Air Uganda Increases Flights to Dar". Kampala: New Vision. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Administrator (14 October 2013). "Two decades of positive growth for Crown Beverages". The Independent (Uganda). Kampala. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Hazards and vulnerabilities among informal wetland communities in Kampala, Uganda". Environment and Urbanization. 28.

- ^ "Google launches wi-fi network in Kampala, Uganda". 4 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Francis Kagolo, and Joseph Kariuki (24 August 2008). "Deadly Ride: Boda Bodas Leading Cause of Hospital Casualties". New Vision. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Pioneer Easy buses to offer 24-hour service". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Muhairwe, Priscilla (5 April 2011). "Pioneer Easy Bus Set to Introduce Electronic Pay Buses". The Independent (Uganda). Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Pioneer Buses Start Service, Taxi Strike Flops". Welcometokampala.com. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Pioneer buses back: What has changed?". Daily Monitor.

- ^ a b "Deadly Crackdown on Uganda's Walk-to-Work Protests". TIME.com. 23 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ a b Musaazi Namiti. "Uganda walk-to-work protests kick up dust". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Kizza Besigye held over Uganda 'Walk to Work' protest". BBC News. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ a b Ngwomwoya, Amos (23 February 2018). "Passenger train services to resume on Monday". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Alfred Ochwo, and Mercy Ahukana (27 February 2018). "Kampalans welcome revamped passenger train services". The Observer (Uganda). Kampala. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

Bibliography[edit]

External links[edit]

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kampala. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kampala. |